“Nobody Uses Their Real Name” and Other Outdated Notions

Or: A Personal Reflection on the Past, Present, and Future of Names on the Internet

The Past

I got my first email address in 1991. I was a freshman at UC Santa Cruz and a friend took me to a basement office where you had to fill out a paper form to get your ucsc.edu email account. In the box labeled “User-name” I started to write “Derek.” My friend stopped me. “Nobody uses their real name.” He said it like he was talking to a child.

So that’s how I became floyd@ucsc.edu. (Yes, I used to listen to a lot of Pink Floyd. I was in college!) I was “Floyd” on every email system I used for the next decade. Outside of some early flirtations with identity deception, I never pretended I wasn’t Derek in those places. Having “floyd” as my username was just, as Grandpa Simpson says, the style at the time.

When I launched fray.com in 1996, hacker culture was still going strong and the masses were not yet online. Back then, it was normal to have a pseudonym or “handle” that you went by. Most communication online was hidden behind handles, which it reinforced the idea that the internet was not “real” in the same way real life was. People treated everything online like a game. It was “cyberspace,” not reality.

Fray was about true stories from real life, so it made sense to use real names. I required that our authors use their real names. (We made only one or two exceptions when it was necessary.) It changed what they wrote. They stopped pretending to be something they weren’t. They became real.

(We were so naive back then, we even showed our actual email addresses on comment pages. Email addresses right there on the page for all to crawl! Those were innocent times.)

At some point I started to use “Fraying” for most of my accounts, mostly because I listened to less Pink Floyd and “Fray” was usually taken. I still use “Fraying” for most usernames, but nobody really calls me that. Every time I consider using “Derek” or “Powazek” for account names, I still see that look on my friend’s face 20 years ago.

The Present

The idea that the internet is a place that’s separate from reality has faded. People generally have online identities that map to who they really are. Outside of a few legitimate edge cases and the occasional sci-fi fantasy, who we are online is simply who we are.

Facebook has done more to influence this than any other site, and I’m glad for it. When someone in the mainstream media quotes a tweet from “SexxxyDude3030” it only reinforces the idea that people online are idiots you only talk to when you’re covering the latest dumb trend story.

Recently Google launched a Facebook competitor called Google+ (a name I hate writing so much, I’m going to just call it “Plus”). And they made two interesting decisions on names.

First, there are no usernames, no handles. Who you are is simply who you are. I think that’s a bold move, and I’m interested to see how it plays out. Facebook also started this way, but later had to introduce usernames to allow people to create unique URLs (like mine, facebook.com/fraying). Without unique usernames, Google Plus has had to use nonsensical strings of characters (like mine, plus.google.com/100817955763300677682). Clearly the named URLs are better, but it also introduces a land-grab mentality, and when you start a service that plans to host millions of people, having all the good names taken is a real concern.

Second, Google is asking people to use their real names. The official policy is to “use the name your friends, family or co-workers usually call you” which is entirely reasonable. Unfortunately, the policy has been enforced in a manner that could charitably be called “error-prone.” When people have to start reverse engineering the rules, you know things have gone sideways.

In any new community system, it’s up to the founders to set the rules they think are best. It’s then up to us to decide whether to participate or not. And while I believe both of these decisions (no usernames, only real names) were made with good intentions and an honest desire to create a better community experience, the combination results in a few sticky wickets:

- The member’s real name has to hold the entirety of their identity. So if someone only knows me as “fraying” I may be difficult to find, and I may not feel that my profile really represents me.

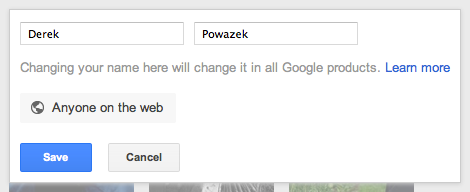

- The real name you enter into your Plus profile isn’t just used for Plus – it’s used for all of Google’s services. Change your name to “Bob” in your Plus profile, and then send a mail from Gmail, and it will go out from Bob. This is very confusing for people who are used to maintaining different names in different places, and it places additional pressure on Plus.

- If, for whatever reason, I am someone that cannot use my real name online, it means I cannot use Plus at all. If I do, I might accidentally reveal my name when I didn’t mean to. And if I use a fake name, I could get my account yanked.

It’s worth acknowledging that Google’s got a uniquely hard job here. Usually a community startup has a period of slow growth where they can work out their tools and policies. People forget that both Twitter and Facebook had years of obscurity to grow organically before they became household names. Anything Google does is immediately front page news. It’s impossible to get a community system right on your first try. People are just too unpredictable in groups.

Fortunately, I think there are some easy solutions for Google.

They could use the same privacy widget for real name that they use for almost every other piece of data on your profile. The widget allows you to set who sees what, and it’s the best of breed I’ve seen in any social network. (That they didn’t use it for real name shows how important they think that information is.) There’s a chance this could happen. The widget is already on the real name field, it’s just stuck on the global setting. At launch, Google Plus also had the gender field stuck on global, and they changed it after getting a lot of negative feedback. Maybe they could use it here, for the last name at least.

They could use the same privacy widget for real name that they use for almost every other piece of data on your profile. The widget allows you to set who sees what, and it’s the best of breed I’ve seen in any social network. (That they didn’t use it for real name shows how important they think that information is.) There’s a chance this could happen. The widget is already on the real name field, it’s just stuck on the global setting. At launch, Google Plus also had the gender field stuck on global, and they changed it after getting a lot of negative feedback. Maybe they could use it here, for the last name at least.- They should allow the Plus profile to be independent of your greater Google account identity, at least for now. In a conversation with Tim O’Reilly today, Bradley Horowitz, VP Product for Google Plus, repeated that Plus is in “limited field trial” and asked for patience, which is absolutely fair. But if the service is limited, then the information I enter there should also be limited. Take the pressure off Plus by letting their profiles be separate from the rest of my established Google identities.

- For the love of all that is good and holy, hire a community manager and empower them to speak frankly to the community and to the company about what’s going on. Community management is a specialized skill, different from product management and engineering. Your members are freaked out, and when they’re freaked out, they can believe any craziness they read. It needs to be someone’s job to say, in a soft pleasing tone of voice, “No, Google is not breaking into your house to scan your passport.” The communication with the larger community has been atrocious, which is unforgivable when you’re building a communication platform.

I’m sure there are people at Google who have thought of all these things already. It’s always easier to sit outside a giant community system and say “this is how it should be” without knowing the specifics. Community management is the process of making decisions with good intentions and then cleaning up after the explosion. Google has smart people who have thought deeply about this, and they’ve shown a willingness (albeit a quiet one) to make changes. I hope they continue to.

The Future

I think we’re witnessing a fascinating shift in online culture. The era of hacker handles is over. We’ve grown out of it the same way I grew out of Pink Floyd. (Even though I still listen to Animals occasionally. It’s the sheep.) The internet is not a second life anymore, it’s your first one. You don’t slip into a pseudonym when you use the phone, why should you be someone else online? Hacker handles were training wheels, and they’re off the bike now whether you like it or not.

This doesn’t mean that there will be no anonymous or pseudonymous conversation on the internet. There will always be a need for anonymous speech, just as there’ll always be a need to pay in cash. It’s just not up to giant multinational corporations to provide that for us, nor should we trust them to do so.

There’s no denying that this has huge implications for how we live our lives, the data trails we leave, and the privacy systems we’ll need in the future. But that future is coming no matter what rules Google decides to implement for Plus. I’d like to see us spend more of our collective energy building that future, and less beating up on Google for their mistakes.

It’s important to remember that, as big and powerful as Google is, the internet is bigger and more powerful. It’s still a big web out there, and every community that feels unwelcome in Plus is a potential audience for someone else’s startup. Don’t like the rules of their playground? Go build your own. The web still gives everyone the opportunity to build something great, using whatever name they want, whenever they want. No one is stopping you.

Other Notes

- If you have an hour to kill, watch the video conversation between Tim O’Reilly and Bradley Horowitz about Google Plus I mentioned earlier. There are some great ideas in it, especially in the latter half.

- I started thinking about all this stuff on Google Plus yesterday, which resulted in this very strange but ultimately interesting thread. Thanks especially to Danny O’Brien for sharing his unique insight.

- Jillian C. York from the EFF makes a convincing case for pseudonyms which I mostly agree with. Pseudonymous speech is important and there’s lots of it on the internet. Whether Google and Facebook implement it is up to them.

- A thought I wasn’t able to work in above: The de facto standard for most current online community systems is that there’s a first name field and a last name field and members can put whatever they want in them, and they only get reviewed if someone complains. It seems to me that this can and should be done better. At least Google is trying something here. Even if it fails, it’s still an interesting experiment and I appreciate that.

- Alexis Madrigal at The Atlantic posted a great thought experiment a couple weeks ago that’s quite germane to this discussion.

- Because someone’s sure to ask: Comments are currently disabled on powazek.com. Here’s why. I encourage you to post your thoughts on your own site. Don’t have one? Get one. That’s kind of the point.

- UPDATE: A fellow alum tweeted me to point out that UCSC no longer allows students to choose their own email usernames. Now they’re just assigned one that’s their first initial, middle initial, and last name. Another nail in the hacker handle coffin.

Derek Powazek has been designing and building community systems online since 1995. He is the author of Design for Community: The Art of Connecting Real People in Virtual Places. The views expressed here do not reflect his company, Fertile Medium, or its clients. Just his. And he’s not entire sure about them, either.